Camp Leftovers: Part 2. Dad’s Life in Poston

Poston Memorial Monument was built in memory of the nearly 18,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated there in WWII. Dedicated in 1992, it is the result of a collaboration with the Poston Community Alliance and the Colorado River Indian Tribe (CRIT) who donated the land for the monument. The concrete pillar symbolizes “unity of spirit.”

Eighty years ago in September 1945, my Issei and Nisei family members left Poston, AZ to “go home.”

Three and a half years before, on February 19, 1942, Executive Order #9066 signed by President Roosevelt forced them to leave the Westminster farm. From that day until May 17, 1942, our family tried to make plans for an unknown future in an undisclosed place for likely the rest of WWII, though no one could imagine how or when the war would end.

This brick at the Poston Memorial is in honor of my Munemitsu family. Camp 1, Block 44, Barrack 6, Unit B was their 20 by 25 foot tar-paper barrack “home” address amidst nearly 18,000 Japanese American families.

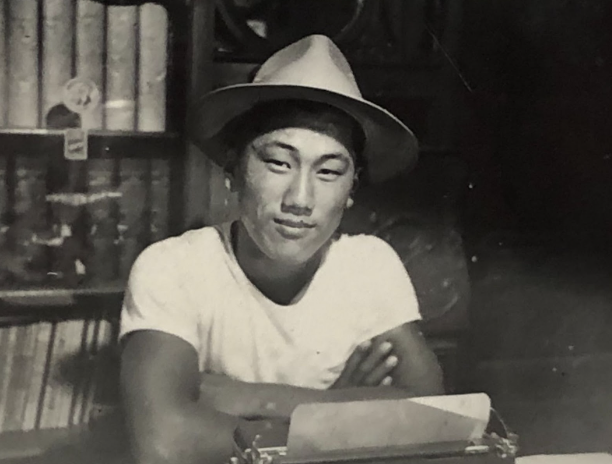

My dad, Seiko Lincoln “Tad” Munemitsu

My dad was just 20 years old, and a young owner of a 40 acre farm with my grandpa. Now they had to make plans to leave the farm with just what they could carry - what would they take with them? What does survival look like in an incarceration camp?

My Dad, friend “Jumbo” Ota, and my uncle Saylo, in front of a Poston, AZ barrack, 1942

I don’t know exactly what he took with him, but this picture at the camp shows my dad with his trusty straw hat, short-sleeved shirt, jeans and work boots. And some tools we’ve always had at our house gave me some clues of what he took and what he did with them.

They were not allowed to bring any weapons into the camp - obvious. But is a hammer a weapon? Is a metal file a weapon? Probably yes if they could be used to strike at someone.

What my dad did was take the smallest hammer head he could find and a sturdy metal file, both without handles. Then he crafted a wood handle for the hammer and a tree branch for the file to make these useful tools. So the hammer head is too small in proportion to the long thin handle, but the tree branch worked pretty well as a handle for the file.

Tools my dad concocted while in Poston: a small hammer head and metal file became tools after he made wood handles in the camp.

I used this hammer for years at my parents house since it was small and easy to use. But it wasn’t until after they passed to heaven and I was clearing out their home that I inspected it closer. On one side of the hammer handle, my dad had carved a “T.M.” for Tad Munemitsu and on the other side, his Poston camp address, “44-6-B.” This small hammer must have been loaned out and made the rounds around Poston Camp 1.

I always wonder of the stories this little hammer could tell - who borrowed it to build a wood table, or put up a curtain rod for the barrack windows. Perhaps someone used it to make some chairs for their small 20 by 25 living and bedroom space or maybe even made some toys out of scrap wood for the children. I’ll never know but this hammer is a symbol of the ingenuity and fortitude of my dad and others to do the best they could with what they had behind the barbed wire fence.

The hammer’s wood handle my dad made in Poston has his initials “T.M.” for Tad Munemitsu and “44-6-B” for his camp address.

Another curiosity that I found after my dad died is this small black leather notepad. While his name was Seiko LIncoln, this was the first time I ever saw him write it as Lincoln S. Munemitsu. He added November 15, 1943, Santa Fe, NM as the date of purchase and location.

After a year in the Poston camp, by filling out a “loyalty” form, my dad was granted “indefinite leave” and allowed to leave Poston to work in Denver under many constraints. But at least he was allowed to work as he tried to make enough to pay for the property taxes to keep the farm as well as provide some income for living expenses for the family not covered by the government incarceration.

It must have been early in his indefinite leave that he traveled to Santa Fe, NM - not for pleasure but to visit his father who was being held in a Dept. of Justice P.O.W. camp.

On May 14, 1942, several days before the family was to leave for Poston, my grandfather was unjustly accused of being a spy for Imperial Japan and arrested by the FBI. He didn’t see the rest of the family for 2 ½ years.

This notebook is an artifact that likely marks the date that my dad saw his father for the first time since his arrest 18 months earlier. Somehow my dad made his way to Santa Fe on a bus. Given the prejudice and racism during WWII, he decided to go by his American middle name, Lincoln, not his given first name, Seiko, to appear more American and less Japanese.

A black leather notebook my dad must have purchased in Santa Fe, NM on November 15, 1943. He put his English middle name, Lincoln, first.

This visit was special because it also marks the date that my grandfather was allowed to leave the Santa Fe Dept. of Justice camp for Denver to work with my father. He was essentially "paroled" to Denver, still having to check in with a parole officer, but able to work and make some money to pay the property taxes for the Westminster farm. While my grandfather was not “free,” it must have been a big encouragement for my dad and grandpa to be together, with hopes and dreams that the war would end and they could go home to Westminster.

There are times I wish these items could talk and tell their stories, the history of where they were, what they experienced. And then here’s one artifact that doesn’t need a story. The fact that it exists is enough story in itself.

Manzanita Wood, cut, polished, and a reminder of “wabi sabi.”

This manzanita trunk from Poston has no real purpose, yet someone cut it, polished it, and it became a camp barrack decoration. It’s not much but a simple work of art. Yet, I see it as a significant symbol of Japanese wabi sabi. Wabi sabi is the appreciation of beauty that is imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete. This manzanita log is a great example of fIndng beauty in imperfection - rather than finding faults, flaws, or brokenness. The idea of wabi sabi embodies the appreciation that nothing is truly perfect or permanent, and yet one can find beauty in the ordinary, the broken, the imperfection of life.

My family’s incarceration camp experience was certainly full of imperfections, injustice with faults and flaws. But in the midst of it, the beauty of the resilience, perseverance, and ingenuity of the Japanese American families and communities was undaunted.

This manzanita log reminds me everyday of the beauty of my family history, as imperfect and difficult as it was. It encourages me to be strong in the midst of adversity, to be resilient and persevere. And it points the way to find the beauty in each day, each month, each year as part of this imperfect, yet beautiful, wabi sabi journey of life.